How to Preserve

Why Well-Transferred Magnetic Masters Still Sound Wrong

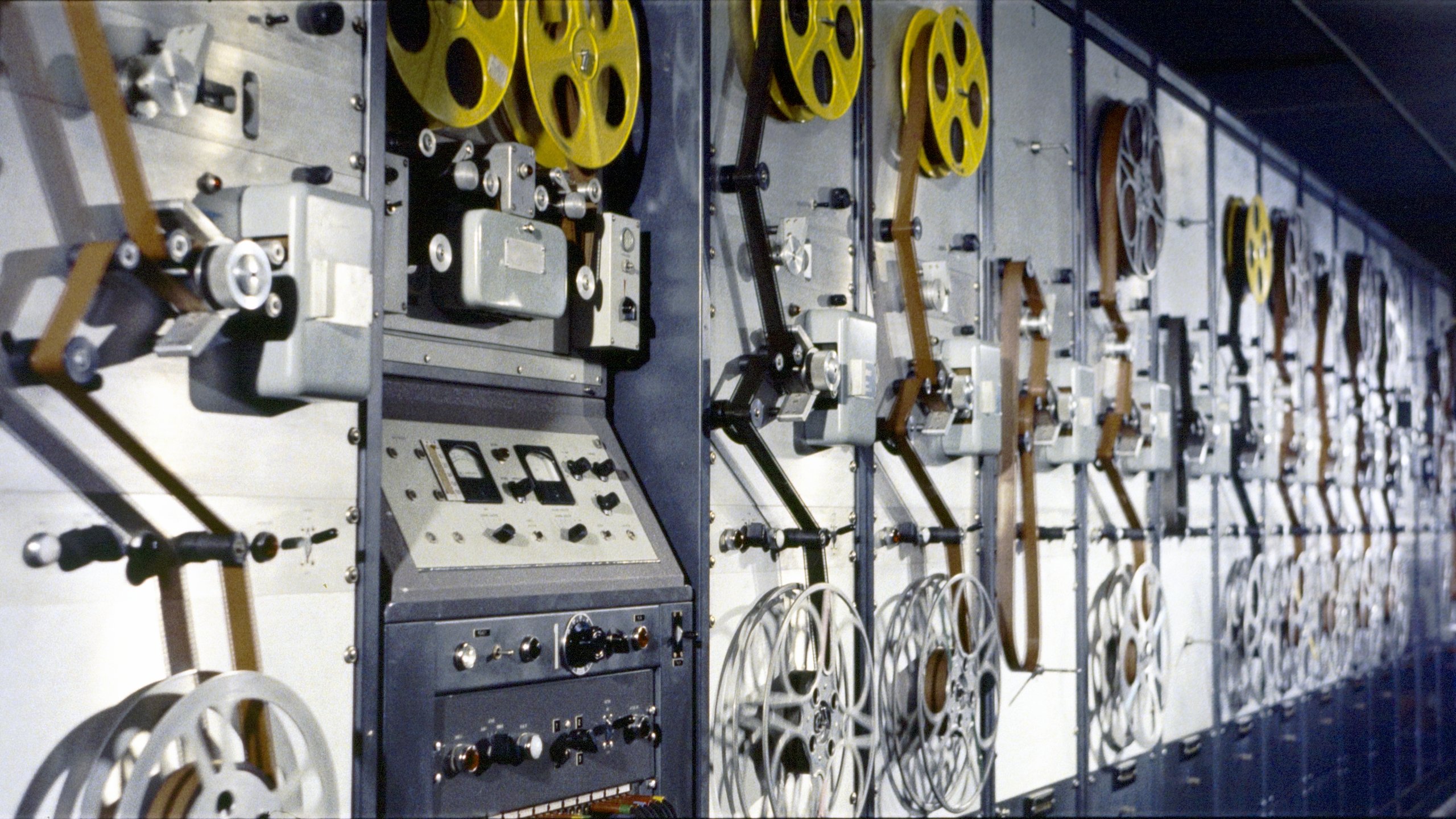

Featured image taken from The Miracle of Todd-AO, 1958

Why do well-transferred magnetic sound recording masters still sometimes sound "wrong" or fail to match a reference release print? In a new white paper on the subject, sound expert and Endpoint Audio Labs founder Nicholas Bergh takes a deep dive into the "secret world" of Hollywood frequency standards prior to the 1980s.

Prior to the Hollywood masters, the contemporary Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers playback equalisation curve was used to record magnetic sounds. Since the industry did not adopt a common equalization standard for magnetic recordings (see SMPTE mag), as well as the recording technology itself, it has been subjected to wild-west practices and applications that are difficult to navigate today.

"If one takes the time to transfer a mag in a way that compensates for deterioration issues as well as correctly compensates for the recording EQ curve used, it is possible to hear a mag very close to how it was heard originally on the mix stage through the entire film" Bergh writes.

This study provides a concise overview of film sound history focusing on magnetic recording, an encroaching technology that gained favor with the broadcasting and music industries shortly after World War II. As a consequence of widespread use of optical sound editing in place from the 1950s, an abundance of optical sound library material at the time, and a workflow built on interlocking systems for synchronization and mixing, the film industry had a longer road to get there.

As Hollywood studios slowly took to the new tech, other variables made industry synchronicity next to impossible. Equipment was leased from one of two companies early on, Western Electric (Westrex) or RCA, and each had different perspectives on best practices. There was also very little documentation about the curves being used internally, and of course each studio had its own philosophies and spirit of modification.

Bergh also references a 1970 Glen Glenn Studios analysis of legacy recording curves, the most comprehensive one on record, and the painstaking process of achieving fidelity to those curves when transferring in 35mm mags today. It's a worthy endeavor, even as today's digital tools make it tempting to speed through the process.

"Most often these days, raw audio transfers go directly to a digital restoration stage, so the preservation or the original raw art object is not always considered as important," Bergh writes. "In other words, there is often a 'fix it in post' mentality when dealing with recording equalization and deterioration. However, when a master mag is transferred carefully, it can sound stunning. It is possible to hear (and preserve) a mix on its own terms before modern digital restoration and reformatting for commercial re-release."

Nicholas Bergh has worked in the audio space for nearly 30 years with experience in remote recordings, music mastering, and film sound restoration for home market distribution. In 2003 he started Endpoint Audio Labs with a focus on improving the quality of digital restorations from the analog side. He is a member of the Academy's Sci-Tech Council Historical Subcommittee as well as the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE), the Audio Engineering Society (AES), the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA), and the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC). He has presented a variety of papers on subjects, including the birth of electrical recording, multi-track optical recording in film, wax cylinder playback, and the technical history of RCA/Victor studios.